In June 1812, Emperor Napoleon marched from Paris with one of the greatest armies ever raised. By the end of the year, what started out as 600,000 troops had dwindled to the mere 25,000 who made it home alive. One can blame disease, a severe winter, and the Russian scorched earth policy for hundreds of thousands of deaths, but in the end, it’s difficult for Napoleon enthusiasts to make credible excuses for this tragic expedition.

In June 1812, Emperor Napoleon marched from Paris with one of the greatest armies ever raised. By the end of the year, what started out as 600,000 troops had dwindled to the mere 25,000 who made it home alive. One can blame disease, a severe winter, and the Russian scorched earth policy for hundreds of thousands of deaths, but in the end, it’s difficult for Napoleon enthusiasts to make credible excuses for this tragic expedition.

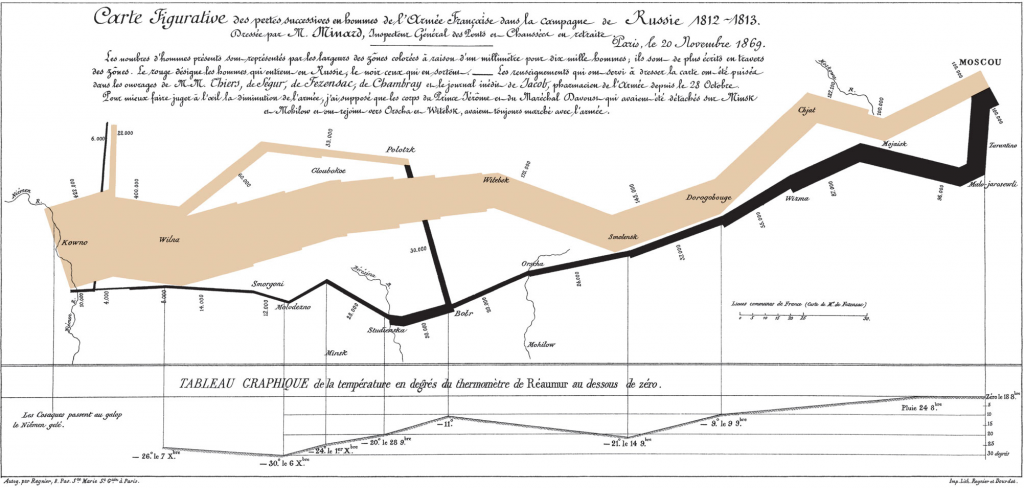

The struggle to understand the disaster gave rise to a famous chart, devised in 1869 by the French civil engineer Charles Minard. The narrowing band of tan depicts the diminishing number of men in the French force during the march to Moscow; the thinning black line denotes those who made their way back. Although recent scholarship has updated some figures, in principle the visual is horrifyingly correct.

For a personal insight on the campaign, I recommend Jacob Walter’s Diary of a Napoleonic Foot Soldier. This two-hundred page volume, which includes current commentary, comes from of the diary of Jacob Walter, a German infantryman conscripted into the Grand Army. In it, Walter provides a vivid yet unvarnished description of the common soldiers’ fight for survival. The text is available in print or as an excellent audio edition.

My 6th ggrandfather was one of the 20,000 something survivors of the Russian Campaign. I am researching the 1812 march into Moscow to try to determine why and how he may have been among those few surviving. Not sure if I can find an answer but it’s been fun “filling in the blanks” as I research.

Good luck with your research. I’ve certainly found the research for my Napoleon novel to be fulfilling and fun.

Pingback: Finding Napoleon in Richmond, Virginia (and Spain) » Finding Napoleon

Pingback: Finding Napoleon in Portland, Oregon Part 2 - Finding Napoleon