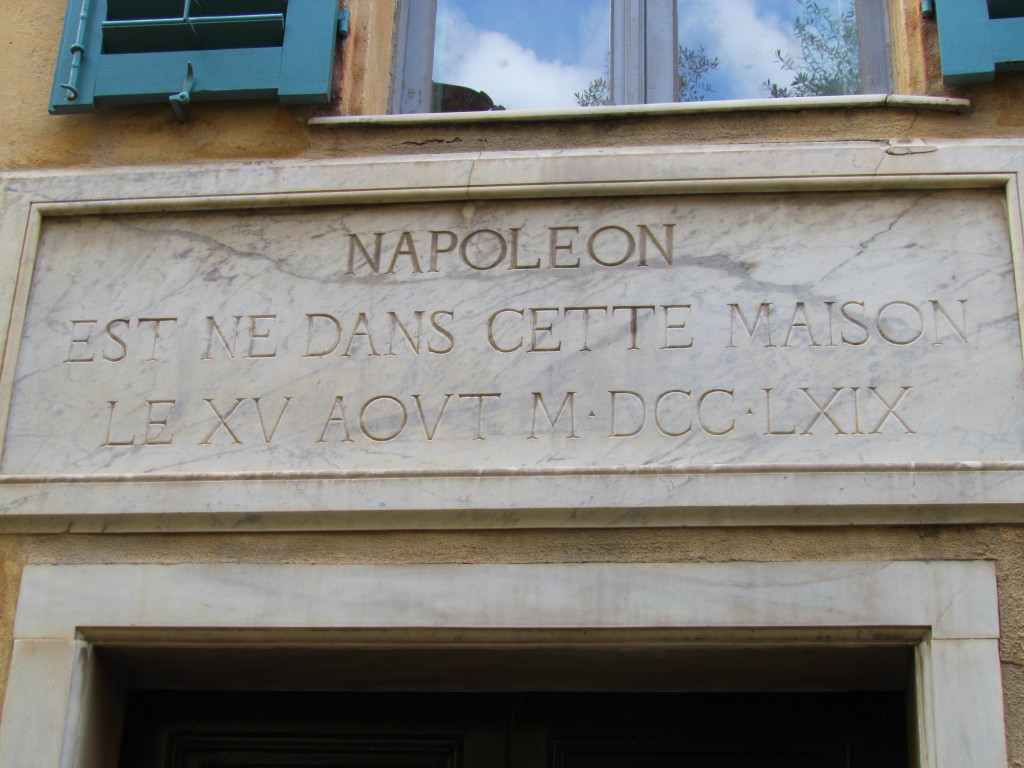

A belated happy birthday to Napoleon Bonaparte who was born 246 years ago, on August 15, 1769, in this house on the island of Corsica.

That lightly-populated island’s strategic position in the Mediterranean led to its repeated conquest and colonization, starting with the Phoenicians in 565 BCE. Over the next two millennia, Romans, Vandals, Ostrogoths, Byzantines, Saracens, Barbary pirates, Greeks, and various Italians followed.

That lightly-populated island’s strategic position in the Mediterranean led to its repeated conquest and colonization, starting with the Phoenicians in 565 BCE. Over the next two millennia, Romans, Vandals, Ostrogoths, Byzantines, Saracens, Barbary pirates, Greeks, and various Italians followed.

In a fascinating coincidence of history, one year before Napoleon’s birth, the Treaty of Versailles ended four hundred years of Genoese rule and transferred the island to France. The Corsicans, who had waged rebellion against Genoa for decades, rose up against the invading French. Napoleon’s father, Carlo Buonaparte, numbered among the rebels. On May 8, 1769, just two months before the future French emperor was born, the Corsicans surrendered. Still, his parents named their second son Napoleon after an uncle who had died in the last major battle for Corsican independence.

Thus, with the thinnest of margins, Napoleon Bonaparte was born a French citizen. Nine years later, due to the support of Corsica’s French military governor the Comte de Marbeuf, young Napoleon entered French military school in Brienne, France. In 1785, sixteen-year-old Napoleon Bonaparte became a commissioned officer in the French Army he was later to lead into both glory and defeat.

But how much of his Corsican roots did Napoleon retain? The proud, rebellious Corsicans have long held a reputation for ruthless violence in the name of honor. The concept of “vendetta”—in strict definition, an honor feud between two families in which the slaying of a member of one family results in the murder of a member of the murderer’s family which in its own turn is revenged and so and on and on—comes from Corsican practices that continued into the twentieth century. Where Frenchmen might challenge you to a duel, a Corsican was more likely to slit your throat—or your brother’s—while you slept. At least that was the Corsican reputation.

But how much of his Corsican roots did Napoleon retain? The proud, rebellious Corsicans have long held a reputation for ruthless violence in the name of honor. The concept of “vendetta”—in strict definition, an honor feud between two families in which the slaying of a member of one family results in the murder of a member of the murderer’s family which in its own turn is revenged and so and on and on—comes from Corsican practices that continued into the twentieth century. Where Frenchmen might challenge you to a duel, a Corsican was more likely to slit your throat—or your brother’s—while you slept. At least that was the Corsican reputation.

As it turns out, it still is. A recent Atlantic magazine featured an article about French license plates, all of which bear a symbol indicating a region of France. Originally, the symbol on the plate was the area where the vehicle’s owner resided. In recent years, an owner has been able to choose any region they would like to display. Now there’s a huge demand for plates with the Corsican Moor’s Head, apparently because it tells other drivers that this is a vehicle owned by a tough guy, “not to be honked at, cut off, or otherwise crossed.”

Yet, for all Emperor Napoleon’s overvaulting ambition, for all General Napoleon’s cold-hearted ability to send troops into bloody battle, he was surprisingly forgiving on a personal level. When his wife Josephine was unfaithful, when his brothers turned on him, when his generals, friends and subordinates betrayed him, he forgave them, often multiple times for repeated offenses.

Sometimes he was being expedient to his own needs, as when he accepted Marshal Ney back to his side in 1815. On the other hand, when after his first abdication his second wife Marie Louise deserted him for another man, he refused to even acknowledge that her perfidy had happened. He could express his anger when Tsar Alexander broke a treaty or when the malicious Talleyrand maneuvered in Europe’s courts against him, but when those he held dear betrayed him, he forgave or turned his head so as not to see. How very un-Corsican.

![By Jerry "Woody" from Edmonton, Canada [CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons By Jerry "Woody" from Edmonton, Canada [CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.mrodenberg.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/FRANCE_CORSICA_ISLAND_Departmental_code_2A_-LICENSE_PLATE_^AT-969-BD_pic_1_-_Flickr_-_woody1778a-1024x236.jpg)