How did Napoleon Bonaparte spend the 2,029 days of his exile on St Helena? After all, the Great Man (or Monster, depending on your point of view) jam-packed his previous forty-six years.

At sixteen, he rushed through Paris’ École Militaire to graduate after one year instead of the normal two. In 1798, on his way to Egypt, young General Bonaparte conquered Malta, where he removed the corrupt Knights of St. John from power, wrote the island a new constitution, freed the Jews from religious prosecution, reorganized the legal system, and set up a French garrison—all in one week.

At sixteen, he rushed through Paris’ École Militaire to graduate after one year instead of the normal two. In 1798, on his way to Egypt, young General Bonaparte conquered Malta, where he removed the corrupt Knights of St. John from power, wrote the island a new constitution, freed the Jews from religious prosecution, reorganized the legal system, and set up a French garrison—all in one week.

Throughout his reign, Emperor Napoleon kept his ministers awake much of the night strategizing campaigns, writing the Napoleonic Code, planning roads and canals, and designing France’s modern education system. He scrutinized budgets, even correcting mistakes in their addition.

No detail was too small, no ambition too large for him to contemplate.

So faced with house arrest on remote St Helena, how did he fill the empty hours? For work, he dictated his memoirs. For his pride, he waged petty wars with the British governor, Sir Hudson Lowe. For his health, he gardened. But for amusement?

Although a prisoner, Napoleon Bonaparte had retained his sword and his dueling pistols. At what must have been a low point for him, he used the pistols to take potshots at rabbits and at a neighbor’s goat that wandered near his vegetable garden. In a happier time, he played at sword-fighting with his young friend, Betsy Balcombe.

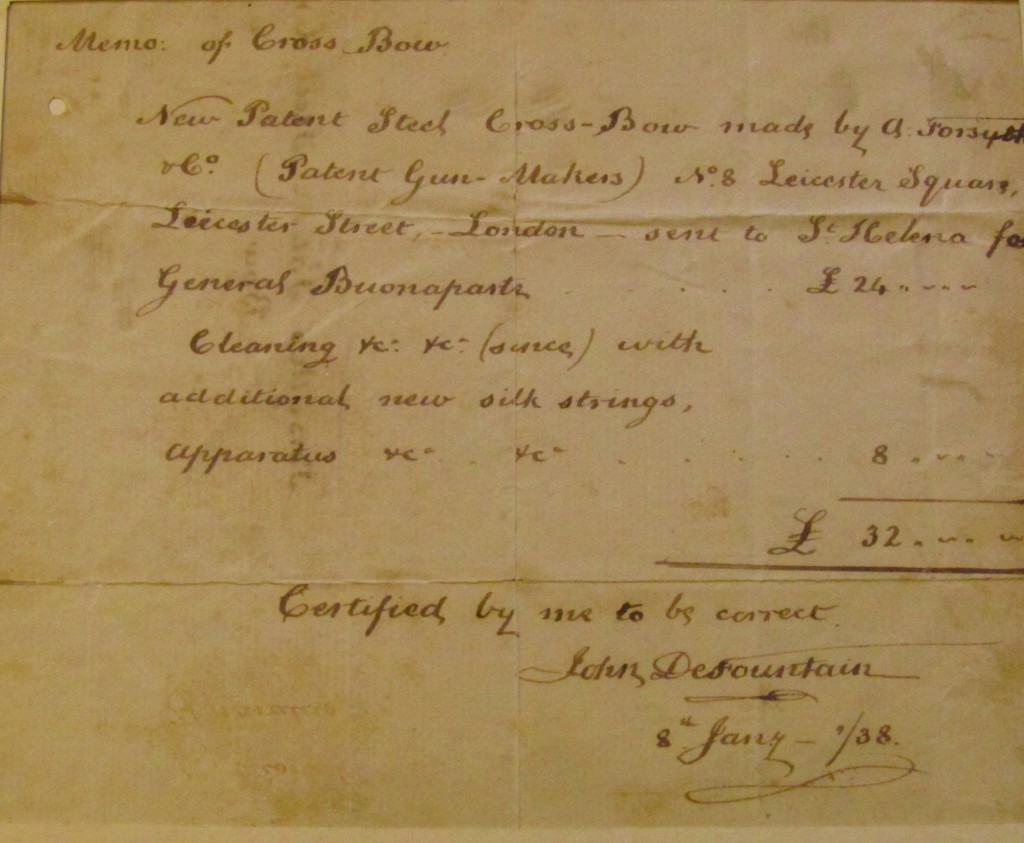

When I visited St Helena’s archives, I found this hint of another pastime: a receipt for the repair of “General Buonaparte’s” crossbow. I’ve never come across mention of a bow in the various memoirs from the period, but I like to imagine a bored Napoleon brightening his afternoon with archery practice.

For more peaceful activity, he played chess with his generals. I’ve read accounts that Napoleon Bonaparte—one of history’s most brilliant military strategists—was a poor chess player and, to appease him, his generals always let him win. Albine de Montholon, the wife of one of those generals, in her memoirs contradicts what she claims was this British propaganda.

For more peaceful activity, he played chess with his generals. I’ve read accounts that Napoleon Bonaparte—one of history’s most brilliant military strategists—was a poor chess player and, to appease him, his generals always let him win. Albine de Montholon, the wife of one of those generals, in her memoirs contradicts what she claims was this British propaganda.

She states that, “It was not easy to play with the Emperor. He marched out his pawns quickly and it amused him to begin the match with unusual moves.” She goes on to say that just when it looked as if he had lost, Napoleon would gain the final advantage using strategy his opponent hadn’t foreseen. That seems much more like the Napoleon I’ve come to know.

Pingback: Napoleon on St Helena: Reading Books - Finding Napoleon

Napoleon’s life in exile [Elba and St. Helena] and out of power interests me. I enjoyed the above essay. I also enjoyed the video of your trip to St. Helena. I’ll be visiting Elba soon. Visiting St. Helena, is unlikely for me; so I appreciate the video.

Enjoy Elba! St Helena, even with its new airport, is quite a commitment. I’d love to go back there.

Margaret

I wonder what you feel about Napoleon’s treatment of Germaine de Staäl. He set the advancement of women back a long way.

My view is that he was a narcissist who caused the deaths of millions and the devastation of Europe.

Still, your call, as they say.

Best wishes,

Nick

(Nicholas Dunne-Lynch)

Hi, Nick,

Somehow, I missed your comment. Really, I wasn’t ignoring you, even though you do ask difficult questions to which there aren’t any definitive (or short) answers. Let me give it a try. And no hard feelings if you disagree!

On women: Napoleon himself said to Madame de Staäl that he didn’t like women being involved in politics. On many other occasions, he expressed views that would be unacceptable today, such as valuing women primarily for the number of children they reproduced. Clearly Madame de Staäl got under his skin and he banished her from Paris. On the other hand, he absolutely valued Josephine for her political acumen. In the end he divorced her because she couldn’t produce an heir (and most probably had lied about her ability to do so.) Were these opinions out of the ordinary for his time? Not at all. Did the French Revolution really make a difference for women’s equality? There were promises but precious few, if any results. Women got to die on the guillotine, but had almost no power and continued to be chattel of their male relatives. Napoleon didn’t improve their position. He was in power for about fifteen years. After his rule, it took France another 130 years to give women the right to vote with the first ballots cast in 1945! I think it’s unreasonable to blame that on Napoleon.

As for blaming all the European wars of his time on him, I think it’s reasonable to look at the fact that Europe had been consumed in war for centuries before he came to power and continued to be after him. During the time he was in power, the European monarchs were determined to destroy Revolutionary France and its ideals, especially that of merit over birthright. I don’t know that he was any more narcissistic or autocratic than the Bourbon kings before and after him or the Austrian rulers, etc. I suggest that he be judged as a man of his time, both for his many faults and his many strengths.

All the best to you and thanks for the difficult questions!

Margaret

Good material here.

Well done!

Thanks, Michael!

Pingback: My favorite Novel about Napoleon Bonaparte (sort of) - Margaret Rodenberg