It wasn’t too difficult to find Napoleon Bonaparte on my recent trip to Berlin.

The city’s iconic Brandenburg Gate gained international prominence on October 27, 1806, when Napoleon Bonaparte paraded his victorious Grande Armée through its arches. Napoleon’s power was at its zenith. He had just won the decisive battles of Jena and Auerstädt. His army marched in dress uniform, while Napoleon, in disregard for his personal safety, rode alone, yards in front, in his humble colonel’s attire. Despite the outward modesty, he felt entitled to some regal Prussian spoils.

The city’s iconic Brandenburg Gate gained international prominence on October 27, 1806, when Napoleon Bonaparte paraded his victorious Grande Armée through its arches. Napoleon’s power was at its zenith. He had just won the decisive battles of Jena and Auerstädt. His army marched in dress uniform, while Napoleon, in disregard for his personal safety, rode alone, yards in front, in his humble colonel’s attire. Despite the outward modesty, he felt entitled to some regal Prussian spoils.

The Quadriga, a bronze statue of Victory and her four-horse chariot by the artist Johann Gottfried Schadow (1764 – 1850) graced the arcade, as it does now. That day in 1806, Napoleon Bonaparte instructed his cultural minister Vivant Denon to send it home to Paris.

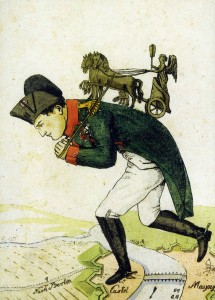

Does that make Napoleon Bonaparte a marauding barbarian? Or a thief as this contemporaneous cartoon depicts him?

Does that make Napoleon Bonaparte a marauding barbarian? Or a thief as this contemporaneous cartoon depicts him?

As early as his first Italian victories in 1796, Napoleon seized art and treasure from his conquered territories. Some he used to finance his army. The rest he sent home to France to fill the Louvre, the first People’s museum, or to pay the bankrupt country’s bills.

Let’s put his actions into historical context. War was the normal state of affairs in Europe. Those who lost paid not only in lives and land, but in cultural treasure. As one small example, a hundred years before Napoleon, just days before the treaty that ended the Thirty Years War, Queen Christina of Sweden spirited out of occupied Prague about 600 priceless artifacts including the Silver Bible, a 6th century book that remains today in Uppsala, Sweden, despite Czech demands for its return.

Napoleon himself forced an outraged Venice to give up the Four Horses, part of another quadriga (four-horse chariot) that had graced St Mark’s Square ever since the Venetians had stolen it from Constantinople in 1204. The Papal States, too, had to pay him dearly for their losses, but they kept the Egyptian obelisk that still stands in the center of St Peter’s Square in Rome. Augustus Caesar seized that from Egypt.

I doubt there’s a major art museum that doesn’t contain or hasn’t purchased some spoil of war, but certainly, Napoleon stands out for the volume and breadth of his war booty. Perhaps that’s a reflection of his success in conquering a broad swath of Europe rich in art and treasure. He had the opportunity and he operated within the social norms of his time.

Our civilization, however, is improving in its morals. In 1899, the Hague Treaty restricted the wartime plunder of most cultural objects. Even that, however, wasn’t codified into international law with legal remedies until after World War II.

As Americans, we’re understandably proud of the United States Army’s Monument Men who disinterestedly promoted the preservation of our enemies’ cultural heritage. Since this well-known photo shows American soldiers discovering art the Nazis had plundered, I was surprised to see the same painting in the Alte NationalGalerie in Berlin. It turns out that particular painting (The Winter Garden, by Edouard Manet) had been legitimately purchased and donated to the German museum in 1896. Nevertheless, after the war, we Americans brought it and 200 other works we’d confiscated on tour to US museums. We did return them to Germany in 1959.

By the way, after Napoleon’s fall, Venice got back its Four Horses. And when the Prussians invaded Paris in 1814, they took their Quadriga back to Berlin. That made it possible for Hilter and his storm troopers to march under the gaze of Victory and her four horses. In the war that followed, Allied bombs all but flattened Berlin. In 1958, the Gate was restored and the statue recast from its original molds. When I was there a couple of weeks ago, it was serving as a backdrop to peaceful human rights demonstrations.

Humanity is still a work in process, as it was in Napoleon Bonaparte’s era, but we are moving forward.

Pingback: Finding Napoleon in Berlin - Part 2 - Margaret Rodenberg