France After Napoleon’s Death:

Even after Napoleon Bonaparte died in 1821, he still threatened the kings of Europe. By declaring himself an emperor, Napoleon had undermined the hereditary “divine right of kings.” Worse, he installed liberal, secular constitutions throughout Europe. And everywhere, Napoleon spread the French Revolution’s concept of “merit over birthright.”

So Louis XVIII of France, King George IV of England, and other monarchs worked to reverse Napoleon’s legacy. But, in 1820, liberal revolutions in Italy, Spain, Portugal, and Latin America reminded them of their precarious positions. When Napoleon died, they feared his burial in France would kindle more unrest.

So Louis XVIII of France, King George IV of England, and other monarchs worked to reverse Napoleon’s legacy. But, in 1820, liberal revolutions in Italy, Spain, Portugal, and Latin America reminded them of their precarious positions. When Napoleon died, they feared his burial in France would kindle more unrest.

They made sure Napoleon Bonaparte—dead or alive—remained on St Helena in exile.

But during the 1830s—an era we know from Les Miserables—France simmered and rioted. In 1840, to appease various political factions, King Louis-Philippe authorized the return to France of Napoleon Bonaparte’s body. Napoleon’s wish to be “buried on the banks of the Seine, in the midst of the French people [he] loved so well” was to come true.

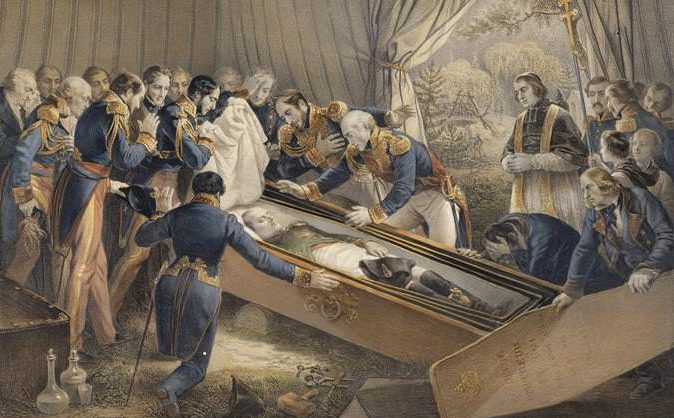

Le Retour des Cendres

One hundred seventy-nine years ago, on December 15,1840, huge Paris crowds witnessed Napoleon’s gilded hearse pass through the city, under the Arc de Triomphe, to the emperor’s final resting place at Les Invalides. Among the spectators was Victor Hugo, the future author of Les Miserables. In a poem, he described the weather “As beautiful as Glory, as cold as the tomb.”

The French call that day Le Retour des Cendres, which translates into “the Return of the Ashes.” But Napoleon Bonaparte wasn’t cremated. In fact, when he was exhumed on St Helena his body was exceptionally well-preserved. The French use the word “ashes” in a metaphorical sense to mean “his remains.”

The Napoleonic Aftermath

A leading politician and writer, Alphonse de Lamartine, opposed Le Retour. In his opinion, “Napoleon’s ashes [were] not yet extinguished, and [the French were still] breathing in their sparks.” He had good reason to be wary.

That very summer, Napoleon’s nephew and godson, Charles-Louis Napoleon Bonaparte, had attempted a coup. As Napoleon Bonaparte’s body returned to France, this nephew—known as Louis Napoleon—began his life sentence in prison.

That very summer, Napoleon’s nephew and godson, Charles-Louis Napoleon Bonaparte, had attempted a coup. As Napoleon Bonaparte’s body returned to France, this nephew—known as Louis Napoleon—began his life sentence in prison.

But in 1846, Louis Napoleon walked out of that prison disguised as a laborer carrying lumber. Two years later, King Louis-Philippe, who had brought back Napoleon’s ashes, abdicated. Alphonse de Lamartine, who led the provisional government, saw his prediction about Napoleon’s ashes verified.

On December 20, 1848, Napoleon’s nephew became France’s first elected president. Four years later, he declared himself Emperor Napoleon III. For the next eighteen years, France would again breathe Bonapartist sparks.

Pingback: Paris Perspective #8: Downfall of the Emperor – the legacy of Napoleon Bonaparte – Pt. 2 – Nouvelles – g7Art224B

I find write up interesting

Even after death Napoleon the great

In a way abolished son of a king be a king