Here we are in the middle of a worldwide pandemic, and too many of our leaders twist suffering and science into propaganda. Look back 220 years. You’ll find the same thing. For example, this painting of “Napoleon Bonaparte Visiting the Plague-Stricken in Jaffa,” by Antoine-Jean Gros (1771 – 1835), makes propaganda from a plague.

In it, Napoleon Bonaparte heroically comforts his plague-stricken soldiers. Fellow officers and a doctor attempt to hold him back from fatal danger. But did General Bonaparte really risk his life to comfort his contagious, doomed soldiers? Does he deserve this heroic portrayal?

As usual with Napoleon, the truth is complicated. And Napoleon’s exploitation of art as propaganda muddies the picture.

Napoleon’s Egyptian Campaign

In 1799, at the tail end of his “Egyptian Campaign,” Napoleon and his troops had advanced into Syria. This grand French invasion of Egypt and the Levant was meant to check British and Turkish expansion. Under cover of extending revolutionary ideals, Napoleon hoped to push his rivals out, and establish French trade and military operations.

But don’t judge Napoleon too harshly for that. In his era and for 150 years thereafter, that was standard practice for European powers.

A mere thirty years old, General Bonaparte understood the propaganda value of his Egyptian campaign. In addition to 50,000 soldiers and sailors, Napoleon took along 167 Savants—scientists, historians, artists, engineers, journalists, and the like. They would tell his story. Plus, the knowledge they gathered would enhance the glory of the expedition. He even brought a printing press to spread his messages to his troops, the local populations, and the all-important audience in France.

Jaffa and the Plague

But back to Jaffa and the plague. Although no one knew that fleas spread the horrific disease, everyone knew the plague was contagious. Yet, Napoleon did visit his suffering soldiers to offer comfort. An eyewitness, Jean-Pierre Daure, an officer in the pay commissariat, wrote that Napoleon “picked up and carried a plague victim who was lying across a doorway. This action scared us a lot because the sick man’s clothes were covered with foam and disgusting evacuations of abscessed buboes.’” (Quoted from Andrew Roberts’s excellent book, Napoleon: A Life.)

So, Napoleon’s physical courage wasn’t propaganda. In fact, at the Battle of Toulon (1793) and the Battle of Arcole (1796), he jumped into the fray. The soldiers loved him for it.

However, the story of the plague-stricken soldiers of Jaffe ends tragically. The combat between the French and the Turkish forces escalated in brutality, torture, and slaughter. When Napoleon withdrew from Jaffa, it was impossible to bring plague victims on the retreat. He advised (and a local doctor administered) fatal doses of opium to some fifty dying soldiers. In Napoleon’s judgment, that easy death was preferable to the death by torture the Turks would inflict a few hours later.

Repercussions for Napoleon

In 1802, when Napoleon was about to crown himself emperor, rumor of that questionable act circulated in Paris. To squelch the unfavorable publicity, the Emperor commissioned the propaganda painting of him ministering to the plague-stricken soldiers.

In her fascinating book, The Caesar of Paris, Susan Jaques writes that “in the original pencil sketch, [the artist] Gros depicted Napoleon standing, holding a plague victim in his arms. The final painting was completely changed…Gros portrayed Napoleon touching the sore in the armpit of one of his soldiers in a miraculous gesture of healing—in the tradition of Jesus Christ, the saints…and the ‘king’s touch’ of French and English royals.”

In my view, that unnecessary transformation of a general’s courage into a god’s power condemns this painting to propaganda from a plague.

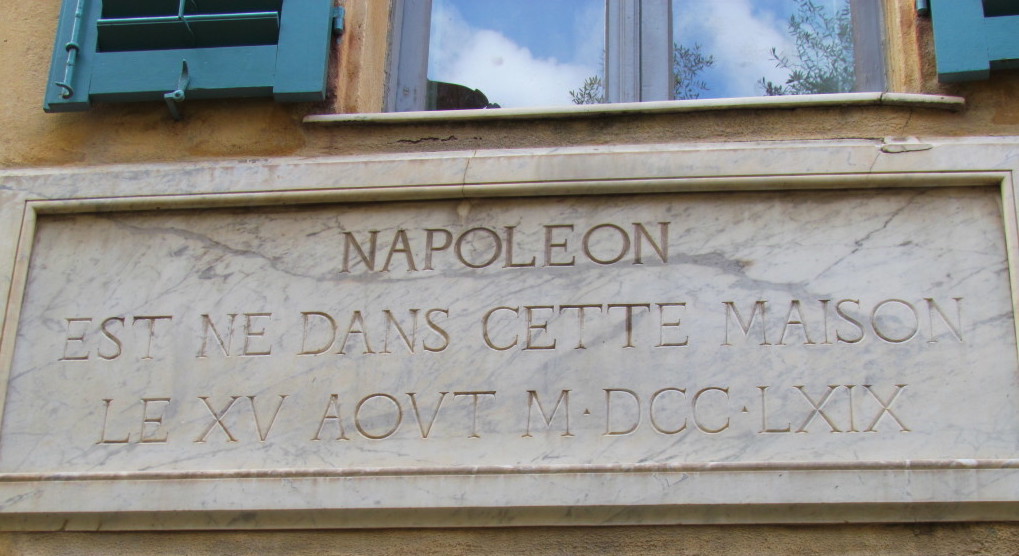

For Napoleon, Propaganda Started at Birth

Today, August 15, 2021, is the 251st anniversary of Napoleon Bonaparte’s birthday. On that day in 1769, Letizia Bonaparte rushed out of the cathedral in Ajaccio, Corsica. From there, she ran the two blocks home and gave birth to her second son, Napoleone di Buonoparte. In some versions of the story, the rug on which he was born had woven characters of Julius Caesar and Alexander the Great. But that’s just propaganda, of course. And an example of Napoleon’s need to embellish an already-good story.

This is an interesting story, and provides insight into Napoleon’s character and courage, and shows his compassion for his troops–and the limits of it. The fact he did not become ill from the plague is not terribly surprising. Infection from the plague comes from two main sources: the bite of an infected flea (bloodborne transmission) and from inhaling the exhaled aerosols from patients with the pneumonic form of the plague (shades of other pandemics). Touching the pus from a bubo would probably not infect through intact skin as long as the hands are washed within a reasonable time. Thank you for sharing the story!

Thanks for the insight, Dr. Andrews. Napoleon himself said it was a matter of will–but then he would say that!

Margaret